Friday, December 15, 2006

Friday, December 01, 2006

Tax a pair of Gondoliers

ENO's The Gondoliers

Gilbert and Sullivan managed to get over their penultimate quarrel and wrote The Gondoliers. Great success. After which they had their ultimate spat over that wretched carpet. The new operetta ran for 554 nights in the Savoy Theatre, which had been built on the profits of Pinafore, Mikado, The Pirates and Iolanthe. But the premiere of The Gondoliers was the best yet; Sullivan wrote to congratulate Gilbert; Gilbert wrote to congratulate Sullivan. “It gives one the chance of shining right through the twentieth century.” Yes, right through to November 18th, 2006 indeed when the English National Opera gave a cracking good performance of a new production in the London Coliseum of the piece that had seen the light of day on December 1889.

The Savoy was only dark during the run on March 6, 1891, when the whole shooting-match went down to give a performance in Windsor Castle, the first theatrical occasion there since Prince Albert had handed in his cards. H.M. was still dressed in black but was gracious and, on this occasion, amused. Beside her on the table was a bound copy of the score and a jewelled opera-glass. She knew the music already and beat time with her fan. The singers were a bit nervous, especially during the number "A Right-down, Regular Royal Queen" but no offence was taken and the artists were all received in the interval.

Ann Murray (The Duchess of Plaza-Toro) & Geoffrey Dolton (The Duke of Plaza-Toro)

The music is one of Sullivan's happiest concoctions, exquisitely wrought with an endless stream of melodies. The score seems full of tunes one knows, the way Hamlet is full of quotations, There is a story that one evening during the original run the composer sitting in the stalls, forgot himself, and started humming. Upon which an irate neighbour attacked him with “Be quiet, sir; I came to hear Sullivan's music, not you, sir". Sullivan had at his disposal only a small orchestra of thirty but the tuttis sound full and warm.

The Savoy was only dark during the run on March 6, 1891, when the whole shooting-match went down to give a performance in Windsor Castle, the first theatrical occasion there since Prince Albert had handed in his cards. H.M. was still dressed in black but was gracious and, on this occasion, amused. Beside her on the table was a bound copy of the score and a jewelled opera-glass. She knew the music already and beat time with her fan. The singers were a bit nervous, especially during the number "A Right-down, Regular Royal Queen" but no offence was taken and the artists were all received in the interval.

Ann Murray (The Duchess of Plaza-Toro) & Geoffrey Dolton (The Duke of Plaza-Toro)

The music is one of Sullivan's happiest concoctions, exquisitely wrought with an endless stream of melodies. The score seems full of tunes one knows, the way Hamlet is full of quotations, There is a story that one evening during the original run the composer sitting in the stalls, forgot himself, and started humming. Upon which an irate neighbour attacked him with “Be quiet, sir; I came to hear Sullivan's music, not you, sir". Sullivan had at his disposal only a small orchestra of thirty but the tuttis sound full and warm.

An unusual feature is that the first twenty-five minutes are without any speech, a concession by Gilbert to Sullivan’s constant pleas that the music in the comic operas be given a more important role. Gilbert wrote to a friend that the new work was "ridiculous" therefore would be praised. And most of the libretto is to be praised; if it is ridiculous, it is also sublime nonsense although occasionally the poet can sink almost to the level of a McGonagall:

"Bridegrooms all joyfully/Brides, rather coyfully..."

And after the quite reasonable ''Ye sounding cymbals clang" comes the unreasonable "Ye brazen brasses bang".

True, the plot is not much more than pegs to hang a flimsy story on and to provide Sullivan with cues for his music, but there are very funny patter songs and some quite daring digs at the Establishment.

Donald Maxwell (Don Alhambra) & Rebecca Bottone (Casilda)

Venice is the scene of course but what little plot there is concerns the arrival of a Spanish contingent of three, the Duke of Plaza-Toro, a ninny (Geoffrey Dolton), his wife (a good part for Ann Murray) and their daughter Casilda (nicely sung by Rebecca Bottone), down-at-heel in the libretto but in this production very niftily dressed, poupée aux neufs, dolled up to tne nines. In the late eighteen-eighties reviewers commented on the pretty chorus girls dressed in shortish skirts but the ENO females looked rather like advanced girls but they sang well and lustily. The handsome chunk pair of gondoliers were Toby Stafford-Allen (a. mellifluous "Pair of Sparkling Eyes") and. David Curry. But the star of the snow was Donald Maxwell as The Grand Inquisitor. Richard Balcombe directed vividly. Pretty costumes and a taking pop-up backcloth of the canals which eliminated the necessity to do a Canaletto-type set. If you are not one of those unfortunates who find G & S anathema, do go to this amiable pleasing production,

G & S would be astonished to find that their theatre in the Strand is currently occupied, not by Giuseppe and Marco but Porgy and Bess.

ENO's The Gondoliers returns to The Coliseum in March

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Triumphant Debut by Colin Davis: 28 November 1958

Colin Davis, assistant conductor of the BBC Scottish Orchestra, conducted his first professional opera on the stage at Sadler's Wells on Wednesday night and it was a triumph. The audience gave him a warm reception and the critics in London have welcomed him as an outstanding Mozartian. It is difficult to avoid saying "I told you so" for this column has repeatedly acclaimed his work in conducting concert performances of operas by Mozart, Verdi and Beethoven in Oxford and Cambridge with the Chelsea Opera Group.

Sadler's Wells will be well advised to snap up Mr Davis when his contract with the BBC expires next year for they badly need a conductor with a sense of style and the authority to achieve a lively and well-balanced performance. The debut at the Wells was made with The Seraglio; the music emerged warm, flexible, meaningful and with, above all, an excellent pace and rhythm. The singing, alas, was not in the same class, although it was clearly not for want of rehearsal.

Jennifer Vyvyan sang the fabulously difficult part of Constanze and her musicianship and feeling for the role were immeasurable. Much of her singing was meltingly beautiful except - and it is a notable exception - that she developed a disturbing quick vibrato on nearly all high notes from F upwards. In the interval rumour had it that she has been troubled with asthma recently - that would no doubt account for this unexpected flaw; and we sincerely hope that it is a temporary one.

The other lady, Blonde, was sung by June Eronhill like a parody of a soubrette with a voice like a squeaking mouse. When the two girls sang high together the noise was like one of those Goon-Show sequences with a speeded-up tape.

William McAlpine seemed inhibited. He sang all the notes that Belmonte has to sing very well indeed, but one wanted to put a squib in his pocket, it was so dull. Kevin Miller's Pedrillo was badly sung and his speaking was a silly imitation of a university accent.

There only remains the Osmin of William Clarkson. He was quite unsuited to the part by temperament - there is not an ounce of honest rage in him - yet by applying his usual commonsense to the task he succeeded tolerably well. The staging and settings were quite acceptable.

Aida at the Garden this week brought Rudolf Kempe as a new conductor in this rather ineffective production. Kempe made a very good job of it and showed that he can be exciting when he is not too self-consciously holding back climaxes. It is not easy to approve of his habit of keeping "The Valkyries" down in order to make "The Twilight of the Gods" more telling, and certainly Verdi needs a fortissimo when he marks one - and Mr Kempe obeyed him to the letter.

Lately I have been wondering if the Chorus, for so many years the most stable excellence in the Opera House, is not getting rather lack-lustre. A bit more ginger is wanted. The greatest pleasure of the evening came from the singing of Jon Vickers as Radames and Regina Resnik as Amneris; John Shaw's Amonasro grows apace and Amy Schuard was almost mellifluous in the second and third acts.

The numbers 385, 622, 550 and 551 indicate no mysteries of American football but are the catalogue designations of the works of Mozart that Sir Thomas Beecham conducted in the Festival Hall: the Haffner and the last two symphonies together with the Clarinet Concerto. One came out ecstatic but almost exhausted by so much beauty. Some of Sir Thomas's tempi were on the fast side but they were powerless to rob the music of its validity.

I should like to tell a story that shows a side of Beecham which may not be familiar to all my readers. I rang Mr Brownfoot, Sir Thomas's faithful librarian for many years, to make sure about the first, of the two encores played -it was the March, K.249, with Beecham's own fairly discreetly added clarinets and trombones - and happened to ask him if he had been marking the parts of the G minor Symphony at the time.

The G minor Symphony, No 50, was played after the interval, complete with Sir Thomas's latest emendations. Now this work has been played by this conductor perhaps more frequently than any other Mozart symphony. And yet here he is, at the age of 75, having new thoughts about the work (and I know from experience that this remarking of old parts is a constant process). This is absolutely typical of Beecham. It is no whim of an old man but the continual searching for truth that is the hallmark of an artist ever young in spirit.

Hindsight (HS): The sub-editors of 'The Scotsman' in the London office at 63 Fleet Street were a bunch of nice guys, especially the chief of the genus, Charles Roberts,a highly intelligent man who would have gone much further, the others said, if it had not been for his overuse of the Scottish national elixir. They sometimes cut my stuff, but not often and the fact that my headings were not always used was, they said, the works of the other subs up in Head Office,jealous of my talents: booboos like Mozart's Symphony in G minor No. 50 were rare. Although another notice ended in the air with "the playing of the London Symphony Orchestra was full of..."

Sadler's Wells will be well advised to snap up Mr Davis when his contract with the BBC expires next year for they badly need a conductor with a sense of style and the authority to achieve a lively and well-balanced performance. The debut at the Wells was made with The Seraglio; the music emerged warm, flexible, meaningful and with, above all, an excellent pace and rhythm. The singing, alas, was not in the same class, although it was clearly not for want of rehearsal.

Jennifer Vyvyan sang the fabulously difficult part of Constanze and her musicianship and feeling for the role were immeasurable. Much of her singing was meltingly beautiful except - and it is a notable exception - that she developed a disturbing quick vibrato on nearly all high notes from F upwards. In the interval rumour had it that she has been troubled with asthma recently - that would no doubt account for this unexpected flaw; and we sincerely hope that it is a temporary one.

The other lady, Blonde, was sung by June Eronhill like a parody of a soubrette with a voice like a squeaking mouse. When the two girls sang high together the noise was like one of those Goon-Show sequences with a speeded-up tape.

William McAlpine seemed inhibited. He sang all the notes that Belmonte has to sing very well indeed, but one wanted to put a squib in his pocket, it was so dull. Kevin Miller's Pedrillo was badly sung and his speaking was a silly imitation of a university accent.

There only remains the Osmin of William Clarkson. He was quite unsuited to the part by temperament - there is not an ounce of honest rage in him - yet by applying his usual commonsense to the task he succeeded tolerably well. The staging and settings were quite acceptable.

Aida at the Garden this week brought Rudolf Kempe as a new conductor in this rather ineffective production. Kempe made a very good job of it and showed that he can be exciting when he is not too self-consciously holding back climaxes. It is not easy to approve of his habit of keeping "The Valkyries" down in order to make "The Twilight of the Gods" more telling, and certainly Verdi needs a fortissimo when he marks one - and Mr Kempe obeyed him to the letter.

Lately I have been wondering if the Chorus, for so many years the most stable excellence in the Opera House, is not getting rather lack-lustre. A bit more ginger is wanted. The greatest pleasure of the evening came from the singing of Jon Vickers as Radames and Regina Resnik as Amneris; John Shaw's Amonasro grows apace and Amy Schuard was almost mellifluous in the second and third acts.

The numbers 385, 622, 550 and 551 indicate no mysteries of American football but are the catalogue designations of the works of Mozart that Sir Thomas Beecham conducted in the Festival Hall: the Haffner and the last two symphonies together with the Clarinet Concerto. One came out ecstatic but almost exhausted by so much beauty. Some of Sir Thomas's tempi were on the fast side but they were powerless to rob the music of its validity.

I should like to tell a story that shows a side of Beecham which may not be familiar to all my readers. I rang Mr Brownfoot, Sir Thomas's faithful librarian for many years, to make sure about the first, of the two encores played -it was the March, K.249, with Beecham's own fairly discreetly added clarinets and trombones - and happened to ask him if he had been marking the parts of the G minor Symphony at the time.

The G minor Symphony, No 50, was played after the interval, complete with Sir Thomas's latest emendations. Now this work has been played by this conductor perhaps more frequently than any other Mozart symphony. And yet here he is, at the age of 75, having new thoughts about the work (and I know from experience that this remarking of old parts is a constant process). This is absolutely typical of Beecham. It is no whim of an old man but the continual searching for truth that is the hallmark of an artist ever young in spirit.

Hindsight (HS): The sub-editors of 'The Scotsman' in the London office at 63 Fleet Street were a bunch of nice guys, especially the chief of the genus, Charles Roberts,a highly intelligent man who would have gone much further, the others said, if it had not been for his overuse of the Scottish national elixir. They sometimes cut my stuff, but not often and the fact that my headings were not always used was, they said, the works of the other subs up in Head Office,jealous of my talents: booboos like Mozart's Symphony in G minor No. 50 were rare. Although another notice ended in the air with "the playing of the London Symphony Orchestra was full of..."

Thursday, October 19, 2006

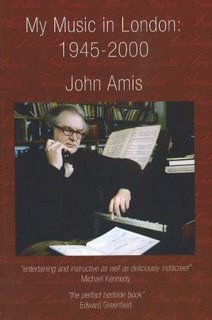

My Music in London 1945-2000: Nicholas Kenyon's review for The Tablet

John Amis has been for a long time a witty and perceptive observer of the musical scene in this country, most recently in the pages of The Tablet. But it comes as a shock to realise, from this hugely entertaining new collection of his writings, quite how far back his encyclopaedic musical memory goes. Here he is assembling players for Benjamin Britten’s Rape of Lucretia in 1946, reviewing the first-ever concert of the Amadeus Quartet, hating Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin Suite, loving Tippett’s Midsummer Marriage, hearing Alfred Deller at the start of the early music revival, and despairing of some of the more recent manifestations of contemporary music.

How the musical landscape has changed over those years! Amis writes warmly of the first-ever performance of a Janacek opera in Britain, conducted by a youthful Charles Mackerras (“a most exciting evening in the annals of opera-going”); he struggles with a first hearing of Boulez’s Structures, losing his way in the score in the distinguished company of Walton and Norman Del Mar (“I am not going to write off Boulez until I can admit to understanding him”). The half-century of which he writes has witnessed seismic changes in the repertory, technology and social role of classical music; Amis, without embarking on grand themes or extensive analysis, just makes us feel exactly what it was like to live through it all.

He always recognised great performers immediately, but was arguably less sure about music (as witness his summing up of the 1957 season: best young singer Joan Sutherland, outstanding young conductor Colin Davis, and best new composer, er, Carlo Martelli). But it is to his great credit that he lets these judgements stand and does not edit them out. He is not afraid to dismiss Messiaen’s giant Turangalila Symphony in 1954 as “a sticky glutinous pudding which appals and fascinates at the same time”, but in the added little postscript notes to his unaltered reviews (called HS for hindsight) regrets making “such a Charlie of myself” by questioning a new Britten song cycle. At heart one feels that Amis responds best to lyricism, to emotion and to melody, perhaps born of his (ultimately disappointed) desire to be a great singer; modernist brutality, however powerful, passes him by.

Old reviews are not as dead as yesterday’s newspaper because they bring the history of performance to life, and that is ever more important now that musical studies are turning their attention from examining works in abstract to discussing actual performances. Here Amis conjures up great moments with Klemperer in Beethoven, and lambasts over-indulgent Brahms from Bernstein. His writing is always cheerful, snappy, down-to-earth, and represents not the views that would make him seem enlightened or avant-garde, but the genuine reactions of the concert-goer in the stalls. The first half of the book contains reviews written for The Scotsman, whose London critic Amis was for two decades. In the second half of the book, more relaxed jottings from recent years, he writes about many of the sacred cows of musical life: Amis saw the need to rebuild Glyndebourne long before they did so, questioned the patronage system in Aldeburgh and so fell slightly out of favour. Benjamin Britten and his uneasy influence loom large here, and of special interest to Tablet readers are two sections about George Malcolm and his pioneering work at Westminster Cathedral, giving the boys voices “the sort of sound they had in the playground”, the texture which inspired Britten’s classic Missa Brevis.

This self-deprecating, whimsical collection of notes from our musical life will entertain all those who have enjoyed Britain’s extraordinarily adventurous and rich post-war scene. The next project should surely be to transcribe some of the countless, revealing interviews with musicians that John Amis recorded over the years. They are now, like this book, a part of musical history.

Nicholas Kenyon is Controller, BBC Proms, Live Events & Television Classical Music

My Music in London 1945-2000

John Amis

Amiscellany Books, £18.99

To order, follow this link.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Myth Conception

Opera it ain’t. But it contains marvels of staging; tech doesn’t get any higher. It is Gaddafi: A Living Myth, given a short run by English National Opera in the London Coliseum (last performances this Friday and Saturday). If you are interested in multi-media of a quite extraordinary expertise and are prepared to submit to undistinguished music that is a mixture of rock and swoopy strings apeing near-Eastern style plus a documentary about Gaddafi which will inform you a lot and bore you a little, then get to the Coli while there’s time. So, if it isn’t opera, why is English National Opera putting it on (at vast expense, will we ever know how much?)? For the sake of novelty, getting backsides on seats including perhaps some ethnic groups who may not care for Puccini or Mozart?

The new offering is of episodes from the life of the Libyan dictator, tyrant, liberator, supporter of terrorism; yet a man that has done his country good, who has earned the commendation of Nelson Mandela and the bombs of America. There is little singing, the story being told (mostly shouted) in couplets, sometimes rhyming, banal often. Shan Khan is credited with the libretto, Steve Chandra Savale with conception and some lyrics. Fatima sings occasionally and there are snappy choruses for soldiers and armed women who do gymnastics. Asian Dub and Diaspora (seven players with electrical instruments) provided the accompaniment as well as a small orchestra in the pit.

Scene one: a group of peasants in the foreground with a backcloth depicting a landscape of a desert. Suddenly the backcloth, by some device of film or whatever, sprouts an attacking army with soldiers, guns, tanks; the apparently one-dimensional backcloth erupts, spouting blood convincingly….. quite frightening. Later on a car breaks through the backcloth; later still the famous green tent, a big one, is erected in a matter of seconds.

Ronald Regan, King Idris, Gadaffi family members, the military are in the cast, headed by TV star Ramon Tikaram as a lookalike Colonel G. in a suitably charismatic portrayal. Mr Blair makes an appearance – and a surprisingly punctual exit! – towards the end. Meanwhile we have, for over two hours, seen much of the myth: the deposition of King Idris, the seizing and maintenance of power lasting nearly thirty years, the determination to spread the Green Book/Koran worldwide, American wrath, war, terrorism, P.C. Fletcher, comic opera uniforms, a spell in the desert and the famous green tent; Gaddafi was a canny choice, considering the many facets of this living myth.

But there is no heart to this portrait, maybe there is no heart to Gaddafi and that is what is lacking here. Even the high tech brilliant staging by David Freeman cannot compensate for the hollowness of the enterprise. The audience roared its approval at the close but I think many of us (especially opera goers) were bored. It is sad that one of London’s two opera houses has put on a show in which music is an also-ran. As with many a film or documentary, you might notice the music only if it were not there. Gaddafi is presumably a one-off: will Covent Garden see it as a challenge to produce something in the same genre? Another living myth perhaps – Castro?

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

Private Passions (Radio 3) Telegraph review

On radio: good company is what makes great radio

On radio: good company is what makes great radio Presenters who make you listen, rather than just hear, are the key to successful programmes, says Gillian Reynolds, the Telegraph's radio critic

John Amis, talking to Michael Berkeley on Private Passions (Radio 3, Sunday) said he nearly died last year and, knowing it, thought to himself: "Well, that's OK. I've met a lot of people, I've heard a lot of wonderful music, I've had some nice sex, I've enjoyed my food. Why not? Goodbye. But I didn't."

So there he was, back on the radio, remembering being taught about life by Michael Tippett and about music by Benjamin Britten, recalling working all those years on My Music, and how well the team got on though they met only in the studio and didn't socialise outside it, declaring passion was what he looked for in music. To all of which this listener, awed, dazzled and glad, could only respond (quite faintly, seeing it was so hot outside): "Hurrah."

This was one of those conversations that showed why, in this country, we love radio. It's because the company is so good. In nations where what comes out of the little box is mostly music, the chances to get to know interesting people via the airwaves are correspondingly fewer. British radio listening remains very high, with nine out of 10 of us listening an average of 23.8 hours each week, because we like what is on it. An essential ingredient of this successful mix is the people.

These days, if you want to listen to music, there are internet services that can construct you a personal playlist made up of tracks you've told it you like, plus new ones the computer will add, selected to fit your predilections.

Such a service won't give you the company of a John Amis, a Michael Berkeley, a Terry Wogan, a Russell Davies, an Andy Kershaw, a Johnnie Walker. If people like them make you listen rather than just hear, they are worth both pay and praise.

Meanwhile, on Sunday's Private Passions, that friendly neighbouring harbour for freights of music and memories, John Amis was on top form. We don't know him, but radio creates such potent illusions we imagine we do.

As soon as he starts talking, however, we realise all over again that we don't, but, because we love what we pick up from him, whether about his marriage, or Frank Muir's quip about Donizetti's demise, or Denis Norden's genius for timing, or why he thinks Tippett was like Beethoven but Britten more of a "know-it-all" like Mozart, you really couldn't ask for better company.

As soon as he starts talking, however, we realise all over again that we don't, but, because we love what we pick up from him, whether about his marriage, or Frank Muir's quip about Donizetti's demise, or Denis Norden's genius for timing, or why he thinks Tippett was like Beethoven but Britten more of a "know-it-all" like Mozart, you really couldn't ask for better company.

Radio 3 Private Passions website